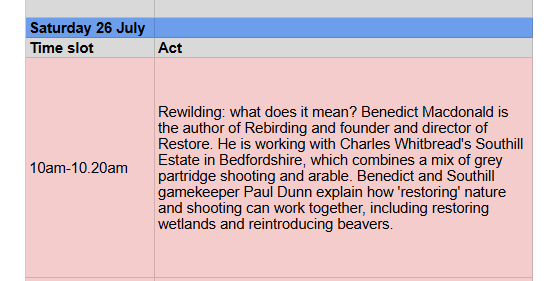

The Game Fair was a meeting place for all those interesting in the countryside (revised July 2025).

Not just in fieldsports, but in all conservation activities intrinsic to the countryside. Away from PR departments, media spinners, membership targets, HQ directives, people from eNGOs, farming, birding, walking, shooting, hunting, fishing interests swapped anecdotal stories, compared notes, and learnt from each other.

It was fertile ground for common ground.

Learning can come from provocative face-to-face conversations held at game or BBC Countryfile events. The debate tent was always a fascinating space – a world away from divisively aired material via remote faceless media platforms – though playing to a partisan crowd was always a risk unless robustly moderated.

We require both evidence-informed science and local knowledge to enable conservation to work today.

Science is vital in conservation in helping allocate funding and guide conservation practice at ‘grass roots’. Satellite tagging (whether cuckoos, hen harriers or woodcock) is one form of data – whereas sharing more citizen data from big garden birdwatch, farmland bird counts, gamebag censuses – can increase engagement and cross-fertilisation between those who may have different values but common purpose towards conserving wildlife.

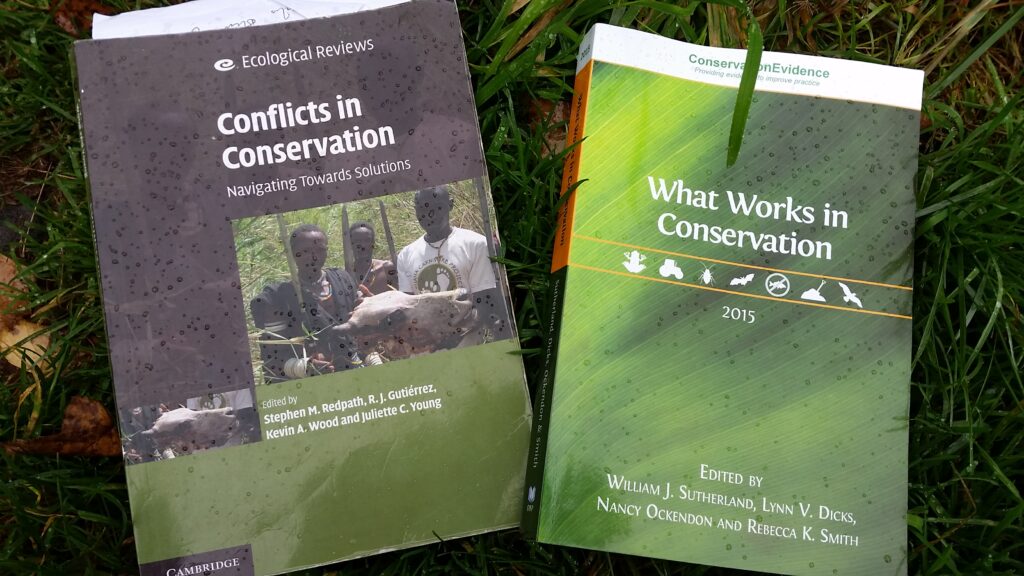

Both these two books are vital – blending scientific evidence from ‘What works in Conservation‘ with the human psychology of ‘Conflicts in Conservation‘ – to help gain traction with land managers of any hue to enhance biodiversity within our human-dominated environment.

If we don’t meet face-to-face so much now, can we at least we learn to collaborate on ‘effectively conserving and managing’ 30×30 (Target 3, see the small print) and work together on the next State of Nature report?

Postscript 2020: in a post Covid-19 online world, the ease of defaulting to tribalism risks cancelling out building trust with dialogue on working together on conservation.

Finally, here are some ways to find a way to dialogue or carve out space for bipartisan in-person events