Conservation is all about human choices. A lightly edited version (with links) of my talk at a Rewilding Symposium held at the David Attenborough building in Cambridge.

“Humans seek patterns and I remember coming across a rock in the Black Mountains with deep grooves in it which I imagined had been scored by rocks in a glacier thousands of years ago. Only after a farmer told me he had “ploughed every field in this valley”, that I realised the marks were from a plough. On another occasion, while walking in the hill, I helped an injured farmer thrown from his tractor as he cut bracken on an impossibly steep 45◦ slope for his sheep. Just as his forebears had.

Why do I mention these two events?

Because as long as humans have influenced these remote hills, we’ve become informed by history. Past policies loom long over us – especially those from the war years – and we must increasingly factor in, provide context as to reconciling policies that drove land use in the past, as to where we are today.

Urbanising indoors

In 1861 the UK was the first country in the world when over 50% of the population started to live in urban areas and today, as an urbanised nation (90%), we have for generations lived in cities, moved out to the countryside, back into the cities then out again. Disconnected from nature (as Alan Watson-Featherstone mentioned), disengaged from food, postcode deliveries to street numbered houses, and the local taxi driver not taking me home because the lanes are too dark, too narrow. All of this creates the perfect frame for a stretched ‘Overton Window‘ – into which politicians and policymakers pitch what they believe reflects ‘the optic‘ of voters’ current concerns. How nature and farming should be equal, self-sufficiency in food is vital and how complexity is easier if dumbed down into simple binary choices.

This is a landscape of ‘rabbit holes’ all with their own ‘wicked problems’. Be careful if you go down one – it becomes a complete warren. Best stay out on top to search for realistic solutions. It pays to understand the past. It took a lot of patience to get hill farmers into the village hall to listen and engage with my talk on rewilding. It took time to walk and talk with National Trust Rangers in challenging them to involve farm tenants right from the beginning in co-owning the processes. Rather than invite them in at a later stage to share the landlord’s new ideas.

And note. The people that need to be in the room may not be the same as those who want to be in the room.

Humans have retreated from being hunters as we’ve urbanised. Fearing even to go near any conversations around the word ‘hunting’, we trawl the fishmonger aisles of supermarkets, trap grey squirrels and baulk at Angling Trust’s campaign for bluefin tuna on ‘catch and release’ in UK waters.

Nature-based hunting

In the context of this conference, a nature-based economy could embrace a sustainable harvest of wild meat through hunting or utilising culled animals. Chairing a conference in Europe on wildlife conservation and hunting (CIC), I met Tovar Cerulli, who’s book (the vegetarian hunter), dwells on the intrinsic role of hunters as conservationists . Yes, that’s me holding up a rabbit or a brown trout proudly declaring ‘this is my trophy!’ (even Monbiot gets hunter’s pride). Don’t disappear down the ‘rabbit hole’ of Cecil the lion, based on moral objections to killing any animal, which distracts us from pursuing debate around really rocky issues on conservation and humans.

Habitat conserved (as Germain Greer referenced), may have come about by hunters preserving it. Enhancing and restoring habitat over generations such as ancient hunting forest refuges which are now Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Let’s not airbrush wildfowlers from the past for all the good conservation they’ve done (Sir Peter Scott), nor ignore 18th Century’s Richard Jefferies as a gamekeeper naturalist, and of course laud a hero to many in the room – Aldo Leopold – hunter, naturalist, forester, conservationist.

Remove the labels

We have more in common than we admit. At the Hay Festival, I asked the Soil Association’s CEO to speak as an organic farmer (specifically not as head of the Soil Association). Sitting alongside an intensive indoor chicken farmer and conventional cereal farmer, all felt freer to discuss commonality between themselves, rather than be stuck in ideological silos. Asked to chair a conference on pollinators, I arrived to discover a heady mix of a beekeeping MP, environmental activists, scientists, farmers and agro-chemical companies. Asking them to take off their labels, not say for whom they worked, I requested 60 secs from everyone on their love/expertise/knowledge on pollinators (before the MP had to depart). The feeling of relief in the room was palpable. Applying the same principle to a roomful of Young Farmers and Naturalists, we all discovered more in common to talk about as well as learn other points of view – on badgers, pesticides, birds and farm practices.

Take the heat

Too often rewilding is used as a weapon against existing land use, rather than as a tool (see my article for Ecos). When a farmer responded to my talk on upland land uses and rewilding – ‘you boy, thirty years I would have had your ‘guts for garters’, it enabled the room to open up on identifying the real issues concerning those in the room. It is better to be part of the conversation – as mentioned by Dafydd Morris-Jones – to ‘get it out’, rather than be overly British and ‘button it’ down.

Let’s not fear negative responses, but embrace tensions, channel them into different places.

Using the right language is important. Size up your audience. ‘Heterogeneity’ (the quality or state of being diverse in character or content), works for academics but not farmers when talking about mixed farming rotations. Let’s not get hung up inflammatory phrases – industrial intensification, nature-depleted, chemical drenched – when it is diversity at landscape or farm-scale in which we are interested and to which Andrew Balmford was referring to in his counterintuitive land ‘spare-share’ talk.

Evidence is important but perception matters.

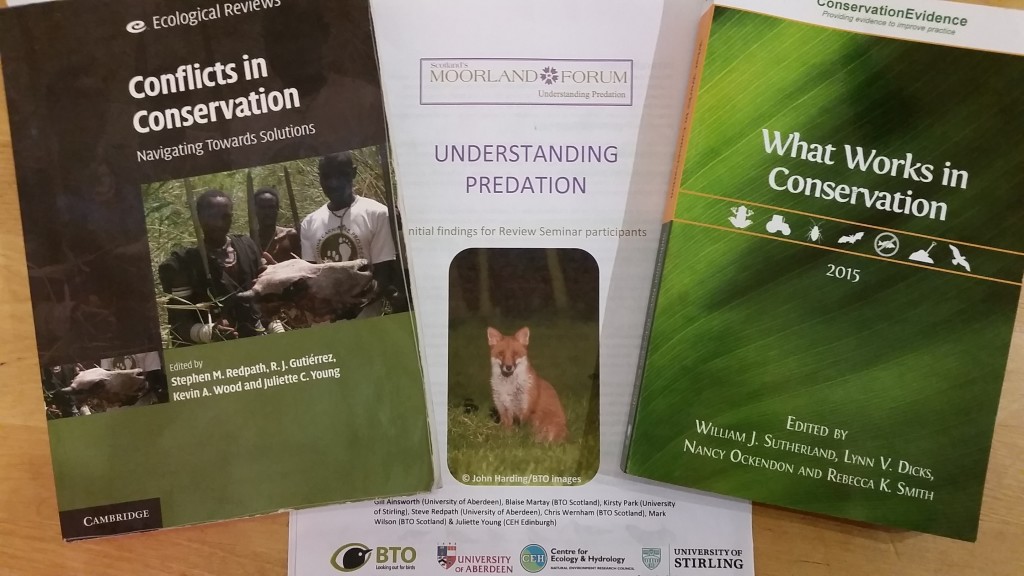

This book, brilliant: ‘What works in Conservation’. It’s got lots of good stuff. But that book may not work that well without studying…….this book ‘Conflicts in Conservation’.

The two books go hand in hand, lots of issues, how to solve them – mainly all to do with humans, not wildlife.

Local chat

Listening to anecdotal is as important as pursuing scientific evidence. Social science, long lost cousin of ecological science, is sorely missed and vitally required for ecological science which can fail to gain traction at grass roots without better collaborative conversations. Because rewilding is all about choices: what do we want, skylark or woodlark? Meadow or tree pipit? We can have better conversations – public opinion is not the same as public benefit, wildlife conservation is not animal welfare – it’s worth spelling out those differences.

There are some inspiring radio programmes which inform better dialogue for conservation. ‘University Unchallenged’ tests our ability to question each other. ‘Tyranny of Story’ is being aware of different narratives in the room at the same time, and allowing an ‘Ability to disagree’ enables us to change our minds. There’s a brilliant TED Talk by Julia Dhar about starting debates on stuff in common, and if anyone is offended by anything I’m saying today, I dare you to enjoy Steve Hughes’ ‘I was offended!’ skit.

It is time to disrupt some of those algorithmic patterns that keep sending us down ‘rabbit holes’, tumbling through echo chambers ending with blind ultimatums – ‘if you’re not with us, it means you’re against us’.

To have better conversations on conservation, my four pointers are:

1. Reconcile past land use policies as to why we are here today. Be informed by them.

2. Acknowledge complexity – as Mencken said ‘for every complex problem there is an answer which is clear, simple, and wrong’.

3. Let go of ownership – there is no moral high ground here, take off your label, loosen up on the ideological stuff.

4. Build trust.

Let’s seek to start more conversations on common ground because….we have more in common than we realise.

Thank you”

Addendum – I undertook a poll at the same time #Rewilding2019 (Jan 19) on “if beavers populated to high nos, would you wear a govt cull approved beaver hat?” with perhaps surprising results (and a refreshed poll with same question in Nov 2020)

Addendum – I undertook a poll at the same time #Rewilding2019 (Jan 19) on “if beavers populated to high nos, would you wear a govt cull approved beaver hat?” with perhaps surprising results (and a refreshed poll with same question in Nov 2020)

You talk so much sense. Keep up the sustainable use vibe. If only more people studied their wild surroundings, whether to hunt to eat, or just to look, they would value and comprehend it more.

Yes! We need dialogue, collaboration, co-operation more than ever before. There is so much at stake here, we cannot afford to dismiss any kind of knowledge or experience. Well written, Rob!