I met with Professor Tim Benton in a tiny cafe at Victoria station, London. I was on my way to Kent from Wales to talk with farmers, whereas Tim was between high-level meetings.

Neither of us knew quite what was about to unfold, nor how pertinent today, three years on, the overarching contents of this conversation might be.

Introduction

Professor Tim Benton is a scientist who was UK ‘Food Security Champion’, IPCC lead author on food/climate/land and is now Research Director, Emerging Risks and Director, Environment and Society Programme at Chatham House (an independent policy institute).

Commodification of farming

Rob Yorke (RY): Farming, whether a small organic farm or a big agri-business, is still an industry?

Tim Benton (TB): Yes

RY: why do we baulk at the word industrialisation?

TB: The post-war global world was, in part, planned at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. Part of the contested discussion was whether agricultural crops should be treated as a commodity, with food eventually coming within the orbit of other goods, services and commodities of the GATT – General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade – the forerunner to the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 1992. Why this is important is because global markets mean the potential for global profits.

(TB cont’d) The incentives for farming has therefore largely moved from being about production of food, to utilising land as an ‘outdoor factory’ to produce commodities for industrial processes. These include the manufacture of food, but includes many other outputs such as biofuels, fibre, feed and, perhaps more in the future, other forms of feedstocks . I was really struck last year at the IPCC land meeting in 2019 that most agricultural ministries represented saw themselves as trade ministries.

After the Scott report in 1942 recommended subsidies for farming, farm output doubled between 1944 and 1974. The increasing industrialisation of farming over the last 40 years has further prioritised growing the productivity of farming. Coupled with synthetic inputs, traditional approaches to land management have been abandoned in the chase for productivity. This has led to large scale single use of land, specialism in farming practices and – until the rebirth of regenerative farming – a depletion of soils.

(TB cont’d) Many farmers growing grain do not know where it goes. The focus on production as agriculture’s primary goal has lead to a concentration in the UK of growing livestock on one side of the country (west) and grain on the other side of the country (east). Resulting in huge manure mountains on one side and low soil carbon on the other side – rather than circular mixed farming enterprises spread across the country, which was historically, more the case.

Misspent productivity

RY: has this pursuit of improving agricultural efficiency and productivity resulted in farmers moving away from mixed farming?

TB: Economic productivity is not the same as growing more: although some farmers may sometimes assume higher yields necessarily mean higher profits. If you want to encourage farm profitability in a sustainable way it very often means finding ways to increase profits from lower yields: either through requiring less costly inputs, or selling to premium markets (or both).

TB: my ‘productivity paradox’ paper makes the argument that by concentrating on efficiency which is effectively productivity at a farmscale – we have incentivised production of ‘more and more’ of ‘less and less’. We have ended up with a super-intensive agriculture which produces an excess of calories and a deficiency of nutrients.

RY: we might come back on this later….

Change ahead

RY: are we in a world which is changing faster than ever since WW2?

(Editor’s note: this interview was originally undertaken pre C-19, Ukraine war, cost of energy/living crisis – see footnote at end)

TB: someone from the Treasury told me recently “we are just starting to realise how big a macroeconomic change is necessary to deliver an economy that is fit for purpose in the second half of the century”.

If you look 20 years ahead, it is going to be radically different. Many parts of the farming community wish for it to be exactly the same. So the mindframe should not be about “I want to carry on being paid ever more for doing the same thing in a marginally different way”. It is about farmers saying, “the world is changing very fast, how can I get my business fit for the new market drivers?”

(TB cont’d) From technological, from the geopolitical, from an environmental, from a climate perspective – the future is about doing things differently.

Birds and bees

RY: is “doing things differently” made harder by the continual messaging of say ‘farmland birds still in decline’ – especially when the nuance of the decline slowing (Defra April 2023) may not be reported?

TB: one of my first big studies was about the decline in insects (link 2002), and the role agricultural intensification may have played.

(TB cont’d) Farmland wildlife needs somewhere to feed, nest, breed and overwinter, and often these habitats may be distinct. Landscape-scale “big farming” result in the diversity of habitats being too small in extent and too fragmented to support wildlife populations around the margins of intensively managed fields. Some farmland birds, such as grain-eating yellowhammers, require high protein insects to feed their young and so feeding and breeding habitat need to be in close proximity.

But over the decades, the industrial-scale use of pesticides (such as DDT in the 70s, chlordane in the 80s, and neonicotinoids in the 90s) have had a negative effect on insects abundance – directly – or through removing their food plants (overuse of glyphosate). This coupled with the homogenisation of landscapes reducing habitat availability has resulted in insect populations crashing.

Habitat sink

TB: So with less available ‘nearby local’ insect food and further distances to fly (at higher risk of predation), chicks may fledge in a worst condition. Chuck in some nasty winter weather restricting their ability to forage, and even if the breeding success looks OK, fledging productivity is reduced which has a negative knock-on effect on overall populations of farmland birds.

(TB cont’d) Though of course farmland birds are only a very small part of the biodiversity we need to conserve in toto, they are a useful indicator of the general health of the countryside.

RY: have we got so attached to farmland wildlife that tensions arise in moving from open farmed landscapes (say skylark) to open wooded landscapes (say woodlark)?

TB: America has been farmed for about 200 years, whereas UK agriculture is 5 to 7,000 years old resulting in the difference between the communities of European farmland birds and American farmland. Yellowhammers, lapwings and skylarks etc have evolved as specialists within the historically extensive farming habitat. However, over decades of intensification that farmland habitat has been degraded and fragmented leading to specialist farmland species not being able to cope with today’s agricultural habitat.

Tree trade-offs

RY: as rural policies now propose more trees within the open farmed landscape, has agroforestry’s time come?

TB: There is scope for lots more agroforestry. Ten years ago, Defra said it was too niche for agri-environment schemes. Now it is no longer niche. It can come in many different guises. Grazed silvo-forestry pastures, planting for shade, as shelter belts…in hedgerows, in-field strips, fruit trees…integrated planting also maximising carbon storage using trees on any form of farmland.

RY: As long as there are no breeding curlew or lapwing….

TB: This is all about trade-offs. It is about recognising there are huge number of ecosystem services that we value. If we have a carbon goal, which we do, you can reach that carbon goal by removing cows. Or you can reach that carbon goal by planting trees and keeping cows. Now, each one of those has a different set of consequences and trade-offs. The problem is “wicked” in the sense whichever choice is made there are negative consequences. It is not a matter of carbon trumps everything else.

Transition of change

RY: a landscape littered with tough trade-offs; it is going to be tough for some in farming?

TB: So how do you make the workforce resilient enough to be able to move out of one industrial process as in post WW2-centric farming practices as they get eclipsed by today’s societal demands? Although farming is ‘special’ (Editor’s note: see para** below) and can be associated with families which have been on the same land for years, tenancies that have been in continuous family ownership for six, seven hundred years…

RY: It does not mean they are right…as there seems to be an overwhelming urge to radically change this primary industry sector

TB: No, it doesn’t mean they’re right; but if you think about what happened with our coal industry, or steel industry and the pain those communities went through…it is not about avoiding the transition – the change is inevitable, it’s about making the transition “just” – as in fair – finding ways to compensate losers.

The rationale for public support of agriculture, the underlying reason that we subsidise that sector and not other sectors, is to maintain a farming sector in order to provide some level of self-sufficiency to provide food security.**

Food security confusion

RY: do some voices risk stalling this transition by conflating food security with food self-sufficiency?

TB: there is confusion between what is food security, which is supplying healthy food for healthy lives and what is self-sufficiency, which is how much food can the UK grow for UK consumption. It is unfortunately convenient, as a political vehicle, for some people to blur the boundary between the two.

And should we grow most of our food? And the answer, is clearly not, as even if we were self-sufficient, say in a war in-extremis situation in relation to food, we aren’t self-sufficient for fertilisers, agrochemicals or packaging for food or other things like that.

Farmers who cannot ride the wave without difficulty, or they’re unwilling to change, or wish to block it for others, have to be supported through this transition. So, whether it’s coal miners, whether it’s steel industry, whatever the industry, we have to get better at creating the capacity to enable the necessary transition in the fairest way. (Editor’s insert – blog on related issues)

RY: is there sufficient knowledge out there to help inform this transition?

TB: The number of conversations I’ve had with farmers who say I’d love to be able to farm in a different way, but “I’m scared I won’t be able to make any money.” There are upland farmers, meat producers, dairy producers, who are really interested in the “less is better” and premium markets. There are sound examples, both in this country and abroad, where livestock farmers have de-intensified to become more profitable.

Meaty issues

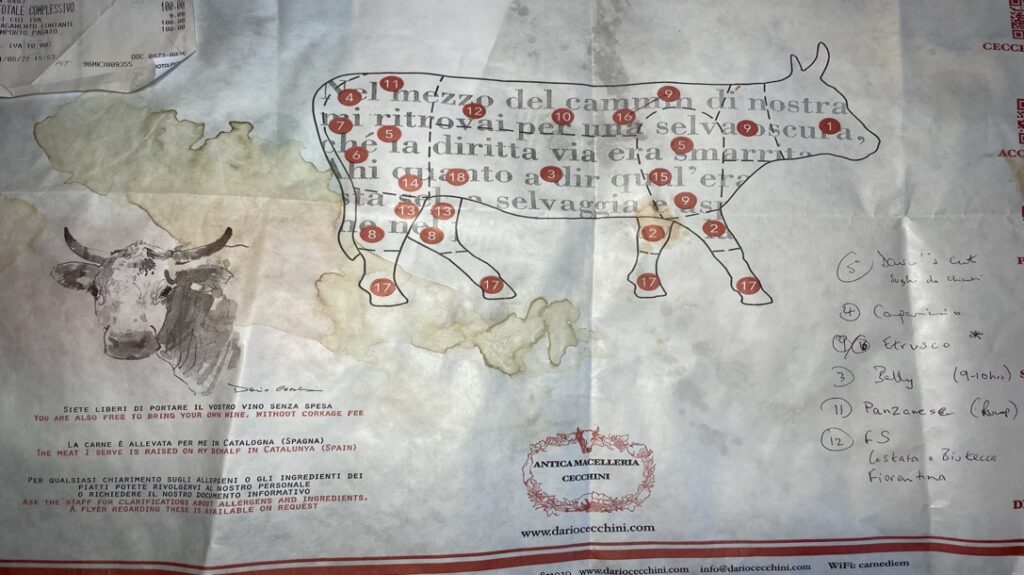

RY: on farming livestock, as the UK exports most of its lamb while importing most of its pork, should we seek to eat less but better quality meat, including more offal nose-to-tail of the whole beast?

TB: We are all trapped within the existing system. One that is designed to deliver calories at the lowest possible cost, whatever the cost. By over-producing grain, we can produce a lot of livestock in ways that we have never eaten livestock before – by calories being so cheap that it is economically rational to feed them to cows. This fuels the demand for meat, which drives all sorts of negatives, as productivity in the narrow sense underpins a wasteful, non-sustainable, health-degrading food system.

(TB cont’d) Because of the economics, there is an excess of low-quality cuts of meat, which are then ultra-processed into sausages, burgers etc

RY: And there is nothing wrong with eating sausages per se, is there?

TB: There is – although there it slightly depends on the sausage – because there’s a strong association between processed meat consumption and cancer risk.

(TB cont’d) So say imagine eating slow-grown Belted Galloway. It is such an investment to grow you’d want to eat the whole thing. The prime cuts of meat would be the rare, real treats. The lesser cuts of meat, as simple mince (not highly processed with nitrates) can be the basis of many meals, and the offal – liver, kidneys, sweetbreads – can all be eaten if we recognise the inherent value of the whole high quality beast.

Much of the approach to economic growth since the post-War II era has been to drive up consumption. Industrialisation of food production, as in high agricultural efficiency outputs per unit inputs lowers prices which leads to food (especially calories) being over-consumed and wasted. By contrast the efficiency of the food system, which is all about feeding people sustainably and nutritionally healthily per unit input – is low.

- Editor’s insert: RY’s 2min YouTube conversation with Italian butcher (Dario Cecchini) on nose-to-tail

RY: are you hinting that we would be slightly poorer, but we’d feel healthier and be happier?

TB: Well, part of the future would be to make the ‘better’ (as in healthy nutritionally) foods more available and cheaper, and the ‘worse’ foods (as in unhealthy calories) less available and more expensive, to ensure a household’s food bills would not necessarily be higher overall and both health/well-being and the environment would be better.

Citizen supermarket power

RY: can citizens (as consumers) change retailers when we walk into a supermarket?

TB: no, we can’t really

RY: Are supermarkets leading consumer tastes?

TB: There is a degree of strategic lack of transparency in the food system. It hides the fact that almost all food – certainly in terms of highly processed foods – has the same ingredients which are produced at very high volumes, very low cost. And that’s how industry makes money.

(TB cont’d) A food technologist once told me: “give me some flour, starch, water, oil and I can make it into anything, any texture that you like. Then give me some flavourings and I can make it delicious, and you’ll eat it and we’ll make a lot of profit”

This lack of transparency means that, after working on sustainable agriculture for 30 odd years now, I can’t go into a supermarket and buy sustainable food easily. So you can’t expect consumers, particularly those on a tighter budget, to create the market impetus to change.

The future’s going to be different

RY: so where are the crunch points, the main triggers for change?

TB: Imagine an economy based on the premise: “are we improving the wellbeing of our people?” rather than “are we increasing the consumption of our people for profit?” You would end up with a very different framework of the economy. And that is part of the contention around the green economic transition.

At the end of the day we all react to different market incentives: whether as a citizen buying food that is healthy, a retailer competing with other retailers, or a farmer requiring to make a livelihood.

The impetus to change will come from the politicisation of the issues. Making it politically practicable – vote winning – for politicians to make what are seen today as difficult decisions* required for the future. (Editor’s insert – i.e. Dieter Helm on net zero electric). So you get to a sudden tipping point where people think “look, I’m just scared of climate change, because I’m going to get hurt” and then demand action from politicians.

(TB cont’d) The same applies to farming and food (Editor’s insert: ‘Contested’ Food Systems paper for FFCC). A lot of the future is about correcting past market failures which focussed incentives on externalising costs on health or the environment.

Now, when the twin drivers of unhealthy diets coupled with increasing volatility in food prices set to a backdrop of increasing scrutiny of environmental impacts of large-scale commodity production, the room for change looms large.

RY: is that the ‘King’s Cross moment’*?

(Editor’s note – *after years of tobacco lobbyist-resisted incremental taxation, a fire at King’s Cross tube station in 1987 created the political momentum/’space’ to ban smoking inside public areas. See also Overton window re spectrum of ideas on public policy/social issues considered acceptable by the public at a given time)

TB: yes, that’s the ‘King’s Cross moment’, when a certain percentage of the population expect “the next election to be about the environment” which politicians will then compete on as to how green they can be.

(TB cont’d) It is not a matter of – it’s climate change – or it’s environment – or it’s health: it’s all of them together. I don’t think that debate has come into focus yet. These are three big drivers which when comes down to the politicisation of them and enough people say “we won’t accept” – that’s when push comes to shove and the proverbial will hit the fan.

Suffice to say the future’s going to be different from what it is today.

RY: thank you Tim

footnotes

addendum: In light of major events since the interview conversation in March 2020, TB updated his views in March 2023. Sole responsibility for external links rests with RY, these may be updated, context added, corrections made at any time via RY as Editor. All pictures ©RY except as shown.

other conversations with food/land related academics – Prof Sir Charles Godfray and Prof David Hughes

pingback – RY first interviewed TB at Hay Festival in 2014 with Christine Tacon – pic below – Benton’s quote: “mark my words, in 25 year’s time diabetes will have bankrupted the NHS”