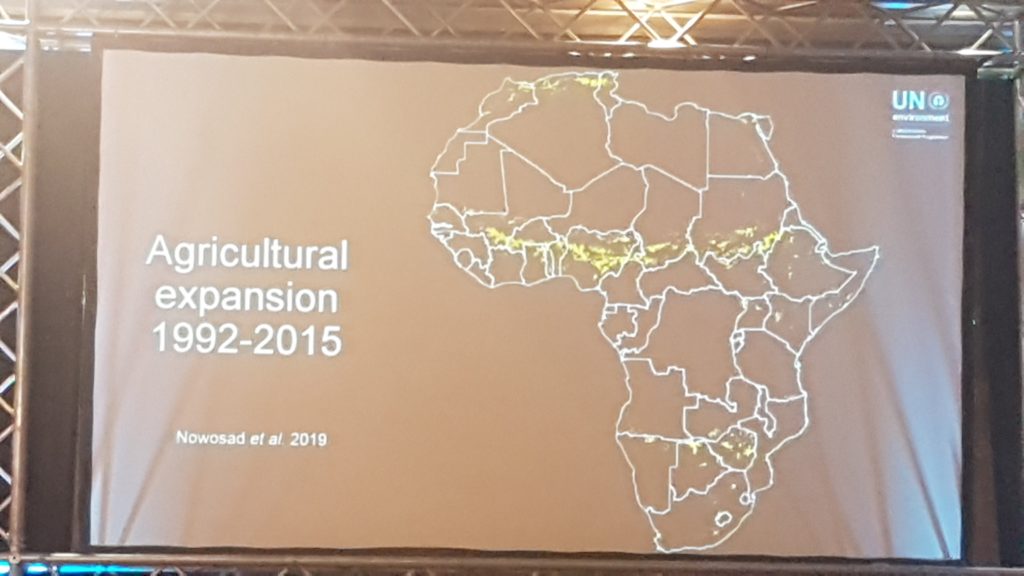

At an African wildlife/conservation/hunting conference, the man from the UN Environment Programme was unequivocal: “if elephants are global ‘public goods’, then developed countries should also pay towards local communities having to ‘manage’ living alongside them”.

Pigeon pie

Plenty of conservation conflicts, tensions, dynamics make the mainstream media. Two years ago Germany wolves were shot if they threatened livestock; monkeys in India bit and stoned two humans to death (culling has failed due to high breeding rate), and in Scotland pigeon fanciers targeted birds of prey which threatened their racers (a welfare charity noting ‘unnatural amounts of pigeons attract unnatural amounts of predators’).

Meanwhile burgeoning populations of red kites and buzzards are persecuted UK-wide and the extermination of red-listed black rats from Lundy have enabled populations of seabirds to rebound.

This clash of humans with ‘threat of wildlife’ is subtly, and not so subtly, being highlighted outside academic conservation scientific circles. However many of us seek to avoid facing up to being the protagonists within increasing tensions on conservation, recreation, resources and land use.

Easier to read the Natural England blog on the health benefits of connecting to nature, than the NE blog on managing wildlife.

It’s all about humans

The late Professor Georgina Mace said in her forward to ‘Conflicts in Conservation – navigating towards solutions’ (a book I managed to slip into an unsuspecting Nature Notebook in The Times): “the apparent conflicts between people and the environment are better tackled by appreciating that the conflicts are actually between different groups of people”.

Arid Namibia

On a work trip to Namibia, my notebook soon filled with crossover thoughts with how we rub up against the environment. Whether farming (managing hedgerows), taking recreation (bikers and capercaillie), enjoying tourism (river users), conservation choices (culling foxes to save curlews), walking dogs (disturbing little terns), developing land (forestry tracks), extracting resources (irrigating lawns), eating meat (see various threads).

No cats, thanks

A rich picking of heady topics for an urbanising ecologically bored who ‘loves-wildlife-but-not-too-close-to-me’. Perhaps less pertinent to a low-density rural populated country where wildlife is prone to bite, kill or kick humans rather than a fox reach the bedroom via a suburban garden.

The issue of nuance in this matter was conveniently ignored by the UN’s Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Its high-media impact press release – ‘Dangerous decline, extinction ahead for wildlife’ was partnered with a simple engaging animated infographic on the five main causes of biodiversity decline. Naturally released well in advance of the actual report, the media had long since moved on for bother with any details.

Reductionist conservation

It’s no laughing matter as we cross planetary boundaries. But I fear ‘science-policy platforms’ are missing a trick by playing to ‘mass mindset’ audiences, while ignoring complex issues around fragile local rural communities living alongside huge thirsty pachyderms.

(Or, to translate to an urbane UK level, how to manage wild boar from trashing nice gardens.)

We seek to govern other practices, put pressure ‘to conform in a censorious age’ – as Lord Sumption said in his Reith Lecture – and use law, not to protect us from harm, but to “recruit us to moral conformity”.

So when you next ask a ‘wildlife management expert’ (aka pest controller) to poison a mouse, trap a mole or remove a fox from your hen run, look outwards and read about another continent. ‘An Arid Eden’, Garth Owen-Smith’s 40 years experience in southern Africa, is a good place to start.

This is less about egos and elephants from Kent to Kenya. It’s more about community-led programmes in ‘developing’ countries which foster co-existence with dangerous ‘public goods’ wildlife we, in ‘developed’ countries, often prefer to view from the safety of our sofa.

First published as guest blog for Knight Frank June 2019

Addendum. See UN/WWF press release (July 2021) Updated with link to WSJ Feb 2026

You maybe are in touch with Prof Adam Hart at Gloucester. He is quite clear that if local people do not benefit from the wildlife that they live amongst, the species will suffer. Hunting is one way to connect them.

Please see

https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2018/dec/20/the-complex-issue-of-big-game-trophy-hunting

A debate that will rage on but ultimately it is about people and their views [which are] often misinformed or informed by their prejudice?

Thanks for your comment Hugh and yes, I’ve met Adam.

There is no one model works for all in this complex field – Namibia do lead in the conservancy-lead model http://www.nacso.org.na/

And other more nuanced mixes of tourism, hunting and other land uses options are being explored https://luchoffmanninstitute.org/2019/10/looking-beyond-hunting-and-tourism-for-community-benefits/ and Wildlife Credits https://www.wildlifecredits.com/

I’ve been involved as a ‘critical friend’ to some of the hunting and wildlife conservation organisations and there is much to do in catching up on how non-hunters are informed (not educated) by intelligent communication from within the hunting community (while also at times publicly outing poor practice).

The future of animals rests in their value, especially the local [human] population whom must co-exist with them. Conservation costs serious money and without value, they will be abused by local peoples as they compete with their crops, animals etc. There are numerous conservation organisations which confirm that big game hunting, for example, are critical to the species survival. That is why Botswana has reinstated big game hunting after 10 years. They realised the best way to conserve their animals is by generating revenue from them and hunters pay far more than photography safaris PLUS bring that to very remote areas that ‘tourists’ can’t or won’t go.

Similarly, selling them to other countries ensures they will NEVER become extinct as the gene poll will be worldwide and able to populate lost local species. Example; the USA has the largest Tiger population in the world. The UK has preserved 3 deer species and are now reintroducing them back to their home land; Chinese Water Deer, Reeves Muntjac and Pere Davids https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/P%C3%A8re_David's_deer

The film ‘Trophy’ by Shaul Schwarz & Christina Clusia; it does an uncomfortable but great job at balancing game hunting vs its global ban. The Directors were anti-hunting at the start of their project. However, they became convinced about the critical importance of hunting and the value it brought to local communities. On a TV review of their film they suggested a way of resolving rhino poaching was to give every poacher a rhino to ‘harvest’ their horn…as each rhino’s horn can be cut/removed, like finger nails, eight times in its life. Thus, feeding an already established market and ensuring the widespread care of the species…radical maybe but a clear view of balancing local vs global needs.

A couple of links worth watching etc.

https://africasustainableconservation.com/2019/05/17/propaganda-and-the-trophy-hunting-debate-the-case-of-conservation-before-trophy-hunting/

https://twitter.com/AllanRSavory/status/1133034976189059074?s=08