ladybird larva attacking aphid

The countryside should not be a peaceful place. It should be humming with activity. While it’s hard to sometimes avoid humans, the real racket should be insects.

From revered butterflies and bees to reviled wasps and ticks – insects have be hitting the news as much as windscreens 50 years ago.

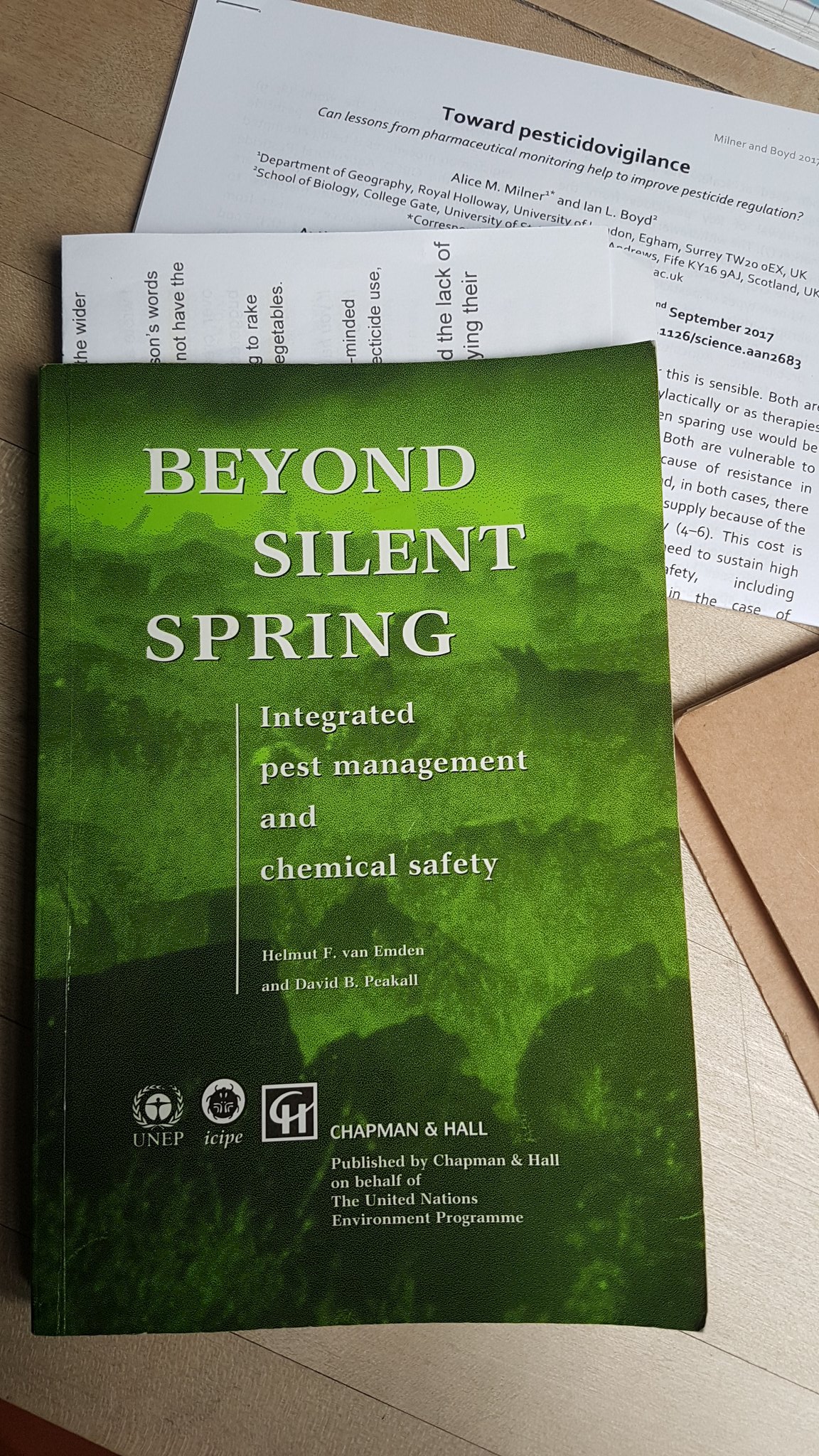

Klaxon classic

Rachel Carson’s 1962 book is worth a re-read. If only to observe the raw narrative, as an early-warning environmentalist raised the alarm on newly concocted chemical insecticides applied without any safeguards. All caution thrown to the wind – blowing chillier when birds dropped from the sky and fish went belly up in rivers.

There’s more in the book than meets the eye. This paragraph caught me unawares (when I’m assuming Carson would be anti all chems. “All this is not to say there is no insect problem and no need of control. I am saying, rather, that control must be geared to realities. Not to mythical situations, and that the methods employed must be such that they do not destroy us along with the insects”.

She adds “It is not my contention that chemical insecticides must never be used.”

Today’s tonic, tomorrow’s toxic

Today’s much accurately applied, highly sophisticated agro-chemicals are hugely efficiently at keeping pest insects at bay. But are also proving to be insidiously persistent in the wider environment.

Overall weights of dosage are down, but toxicity loads are up. Some of Carson’s words ringing true today. In the 60 and 70s, nascent environmentalism did not have the megaphones of today’s broadcasting tools. In any case, society was too excited then of not having to rake beetles out of crop stores, tend fly-blown livestock or handpick aphids off vegetables.

Megaphone environmentalism

Modern media has now wired up that megaphone. And some. To the extent that the internet is not always your friend if you want to explore, with free-thinking curiosity, matters around nuanced issues on insects or judicious use of pesticides. Especially when they are framed within competing narratives on food production, increase of insects pests, climate change, political risk and habitat variables.

Much easier for naysayers to simplify the language, without too much critical scrutiny, translate into apocalyptically headlines and lament the lack of insects mashed on car windscreens.

Much more subtle, way under the radar, is Defra’s former Chief Scientific Adviser’s personal blog. (Unfortunately now deleted due to author’s role on govt’s SAGE Covid-19 panel. Here’s some thoughts from him here and here). He explored the German study on the decline of insects in nature reserves, value of scientific uncertainty, and morality of researching pesticides.

Informed uncertain science

Uncertainty is an inconvenience to a politician’s simple catchy slogan.

A matter Mr Gove admitted when I challenged him in an interview for saying: “there are no tensions between productive farming and care of the natural world”. The use of pesticides is an obvious tension.

But we must heed warning signs around overuse of insecticides, pest resistance, use of commercial pollinators, and the lack of diversity in cropping (aka heterogeneity).

Perhaps rather than rely on ‘a single paragraph’ petitions, we could lobby government to fund new solutions. Get the public themselves to love insects. Push the precision application of pesticides, learn from organic practices, investing in Integrated Pest Management (IPM) – and seek to reduce prescribed prophylactic use of pesticides (including on pets).

Dung and out

I once wrote a gritty blog about dung beetles on the same day the chemist who invented the wormer (avermectin) was awarded the Nobel Prize. Charismatic bees have their champions; but it’s the less iconic ‘bugs’ we need to watch over. Create habitat, reduce chemicals, innovate practices – otherwise we’ll all be buggered by the silence of the flies.

Addendum: Defra consultation on sustainable use of pesticides close 26 Feb 2021 (closed)

First published April 2019 on Knight Frank website. Revise new links/edit Jan 2021, Sept 21

Very much agree with you ….. the same applies with fungi, of course! … for example, the muck we get from our local farmer for our garden nowadays takes ages to rot down, with a sad lack of ‘bugs’, fungi, etc.

Interesting article Rob, but I do have a little nit-pick – you picture titled intra-guild predation is not – intra-guild predation is when two different species of predators eat each other e.g. Harlequin ladybirds eating our native seven-spot for example, instead of the herbivore that you hoped they would :-)

Thanks Simon. You’re right of course and I’ve amended it

(here’s an earlier post of mine on larger ‘red in tooth’ intra-guild https://robyorke.co.uk/2015/07/raptor-brutal/)

Superb article, as always. Rob is our conscience, rightfully so.

What can we do ? I’m bug-gered if I know, but will try (I did save a spider in the bath today!) Well done Rob, never give up.