A pair of nesting long-tailed tits flags up the importance of hedgerows, including debate over their management.

Mine’s a lichen

Long-tailed tits are unmistakable. Bustling with extraordinary energy, their nest activity in a rose-infused thorn-meshed hedge which I struggle to manage, provides joy to many.

While adjusting the nature cam, they would scold me, yet gratefully receive offerings of cobwebs from my office and sheep-wool from the fields. They fought over how the nest should be made – which thorn to weave the web onto, how the moss should sit, even rejecting unfashionable feathers. Enjoy some 10 sec films of long-tailed tits via this twitterX hashtag #hedgegoggle.

Enclosing land

When hedges were remnants of old woodland, to those planted in the 15th century, through to 18th century Enclosure Acts when landlords started to enclose common land – hedgerows have not exactly been symbols of countryside serenity. See Oliver Rackham for early strife around hedges and see X today!

Shifting baseline hedgeline

Managed hedges are just one vital key to sustaining farmland wildlife. Along with protecting livestock from the weather, sequestering carbon, stabilising topsoil, wildlife habitat and multiple other benefits.

These evolving habitats within human dominated landscapes require farmers, as land managers, to cut hedges at some stage. The use of a blade is required. Coppicing to the ground, this reinvigorates new growth from the ‘stools’ which is then laid after 10 years. This may be more than likely then be trimmed or ‘flailed’.

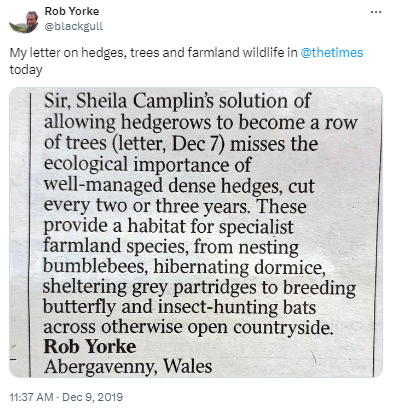

Yes, semantics and operator skills matter! To avoid running into a line of trees, a healthy hedge requires a trim every 1, 2 or 3 years. Here’s a great nuanced thread on the matter and another here (April 2024).

This can result in ecological science conflicting with socio-economic matters, cultural perceptions and carbon capture.

Data is king. Or is it?

Data on birds (such as yellowhammer) nesting seasons, has regulated farmers to cut hedges later in the year. This can incur environmental costs by compacting soils or increase financial costs in seeking to engaged time-poor contractors.

Social media is generally not much help on the issue. Littered with context-free demonising pictures of hedge actions of all standards, few are able to set context or think of the audience –

as to ‘social nuance’ in engaging with three different audiences. From the “mass mindset” to land managers and academia – it’s a thicket of tricky comms.

via blog Acting on land

There’s a lot of the most thornily complex ecological science.

RSPB science says tightly cut hedges protect nesting birds from corvids. This paper from 2009 says birds rebound after hedge cutting, whereas this research says there should be no new hedges near open meadows. Of course, it’s not just about the birds. Hedges are vital for bats, moths and insects.

Right hedge, right place, wrong blade

Adaptively skilled trimming generally works better than prescriptive ‘flailing’. Can we engage in better critical dialogue on how evidence-informed policy is framed within socio-ecological competing narratives from carbon-zero goals to maintaining cultural landscapes?

I’ll leave the final word to a once CEO of the BTO: “To be of most value, scientific findings need a practical application through engagement with stakeholders – often practitioners in the management of countryside.”

Updated Oct 20, March 21, Aug 21, March 24. and some letters on hedges – The Times (Dec 19) and The Guardian (Oct 20)