I could hardly believe what I was seeing. From a public highway, three young hen harriers were riding the breeze over the ridge of bracken bordering onto heather. The story behind them is perhaps even harder to believe. I’ll get to why but first, let’s wind back in time for some context.

A Naturalist’s Sketch Book

Hooky

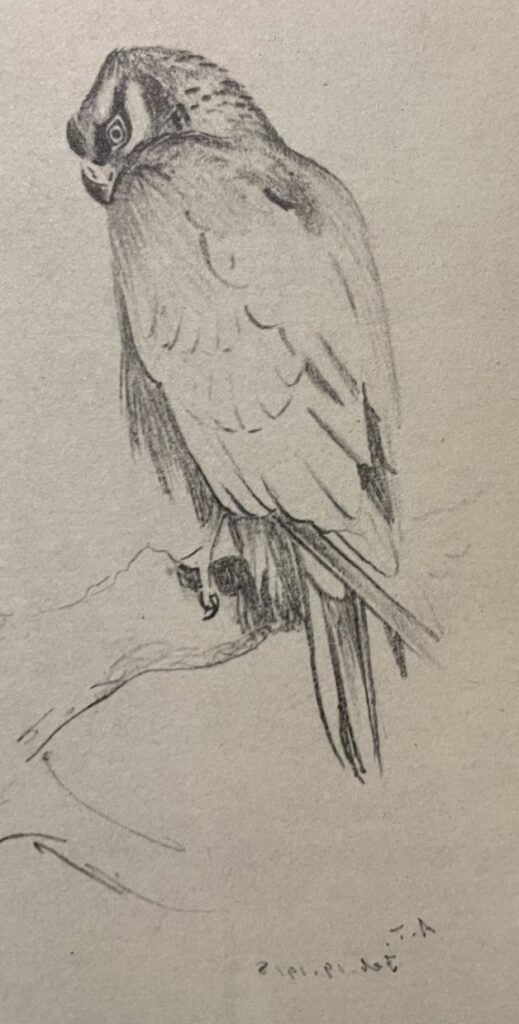

Over 100 years ago, ‘hookies’ as in anything with a hooked beak, were deemed a problem. Much of the human population kept hens in back gardens, poultry farming was in a basic form (note the Great War’s impact on food self-sufficiency was nothing like post Second World War’s push for food – see short vlog on State of Nature 2023) and game birds shooting was in full bore (pun intended). The passage below written by Archibald Thorburn, a past vice-president of the RSPB in 1927, in his sketch book indicates the status of most raptors at that time.

Persecution

As rearing hens in back yards declined, nurturing wild game birds flourished (releasing game birds started circa the 60s). Even the National Trust in the early 50s incorporated legal clauses encouraged sporting tenants to remove magpies and sparrow hawks which might impact on the tenant’s ability, or wish, to pay the rent for a shooting lease.

Thankfully things have changed (see also impact of organochlorine pesticides on birds of prey during ‘Silent Spring’ circa late 60s) but the shadow of fear from raptors still haunts the human mind. Especially those racing pigeons, farming livestock, conserving waders, stewarding gamebirds – see my related guest blog for the RSPB (2016).

Back in the skies

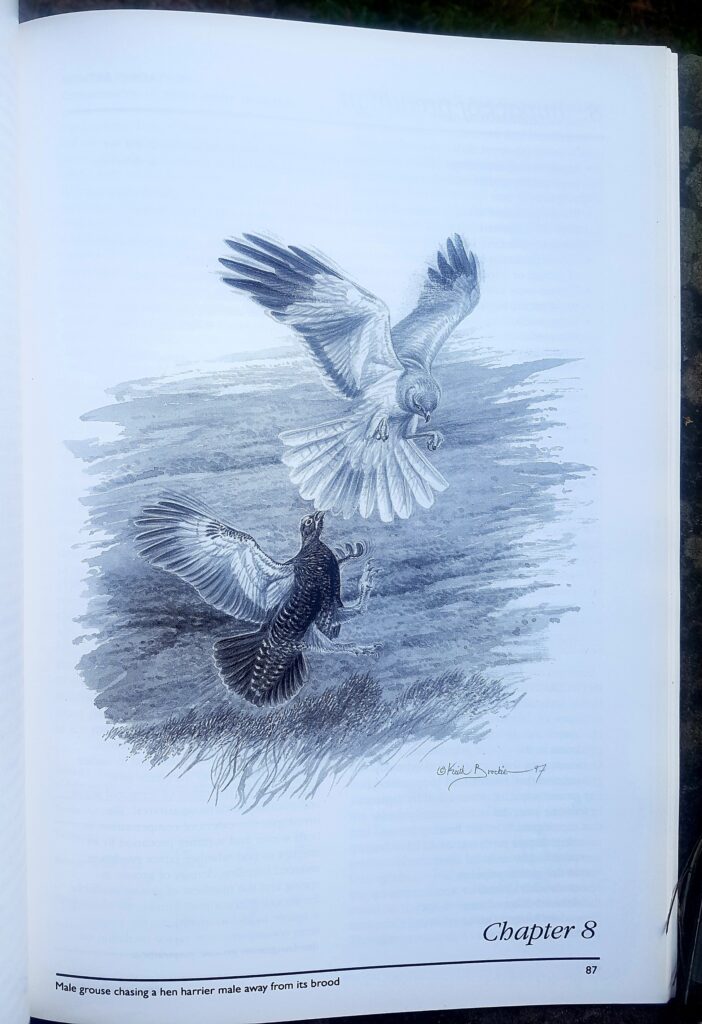

For all the past decline, birds of prey are back in the skies in larger numbers than 100 years ago. Farmed livestock is now mainly indoors (in fact most humans are as well), shooting is more about releasing than husbanding ‘wild’ game birds, and raptor groups keep a watchful eye. Buzzards and red kites, pushed to the west by the indiscriminate use of poison, are flooding back across the UK, golden eagles are returning (reintroduced) to southern Scotland (watch out hen harriers becoming an intraguild snack), goshawks are back in power and ospreys (and red kites) hunt fish from under angler’s noses.

This brings human-human interest tensions (not true human-wildlife conflict, as commonly portrayed), which must be acknowledged and managed towards a co-existence of human interests with provision of wider societal environmental benefits.

Hen harrier’s keeper

That gaggle of young harriers I was watched last year? Oh yes, the grouse moor gamekeeper wanted to tell me the story himself, so I met him and his wife for a cup of tea. The long and short is he found the harrier’s nest on the moor, and returning to show the government agency’s licenced field worker, discovered the eggs had been knocked out of the nest by a sheep. They returned the eggs, later tagging one of the fledging harriers and naming it after his granddaughter. (See footnote below)

One word sums up how he felt – proud. On the return of this raptor, let’s provide the tools and make room for gamekeepers as moorland managers to host more harriers with pride.

“You can never plan the future by the past”

Edmund Burke

footnote – the gamekeeper (aka moorland manager) has informed me one of the immature harriers from that nest of 2022 went onto rear six young harriers in 2023 somewhere on moorland in northern England.

Addendum – RSPB Hen Harrier survey press release March 2024 (full paper published in Bird Study later)

pingback to an updated (2024) blog on raptors (2015). Blog updated March 2024

I was totally enraptured by your story , well done Rob, fascinating as always .