‘The environment in which managers do their job is being transformed: this new landscape rewards some skills more and some less than in the past‘. A line from an article in a magazine last year which resonates with many of today’s rural and environmental issues.

‘If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change’

Giuseppe di Lampedusa, ‘The Leopard’

Soft skills

Executives, managers – from city listed company CEOs, to farmers and land managers – are now expected to employ skills around ‘communication, building trust and showing vulnerability’. While also being comfortable with uncertainty and letting go of being responsible for strategic thinking. Our goal of success ‘at all costs’ isn’t easily geared towards experimenting with failure.

As Richard Feynman said “to develop working ideas efficiently, I try to fail as fast as I can”. Mark Zuckerberg’s also got form when he said “in a world that changes quickly, the only course that is guaranteed to fail is not taking risks” (ref: ‘The Changing Hills‘).

Has a bout of precautionary thinking mixed up with regulatory processes and fear of innovative failure resulted in inertia? Have adaptively co-designed Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes, paperwork-heavy woodland creation, and ‘doom-framed’ State of Nature reports all been in thrall to holding back progress?

Out in the field, things can be very different, and much more positive than is often reported.

In the field

There’s often more happening than meets the eye. I’ve recently travelled across Exmoor/Dartmoor, southern Scotland, Cambridgeshire, Yorkshire, northern Scotland, west Midlands and Cumbria. On these ‘field intel’ trips, I meet a diversity of people to hear and see what they are doing. It’s inspirationally eyewatering as to how much is going on below the radar: by foresters, wardens, farmers, activists, gamekeepers, birders, land agents, facilitators et al.

Quietly managed lowland estate beavers, Scots pine in deer-managed glens, browsable windbreaks hedges, harriers on grouse moors, wild cats in lowlands, worm-rich arable soils, light-touch funded farmland, peat protective cropping, community guided forestry, water company grant-aided ponds all provide hope.

When in a conference…

In a room, things can be different. Speakers say stuff to suit the audience. Understandable when invited by the host. The Bank of England governor quoted a farming luminary saying for ‘farmers to thrive they must have the opportunity to earn a reasonable price to ensure food production in our countryside‘. Yes, but there are also so many new ways farmers can thrive, especially as a land manager – here’s 100sec on just one way and another here.

Backing British farmers is important by buying food which is ‘best’ farmed here in the UK. But it’s not an unconditional pass to ‘business as usual’. While many citizens support British farmers; not so many buy their high quality produce as weekly budgets are stretched between smartphones and steaks.

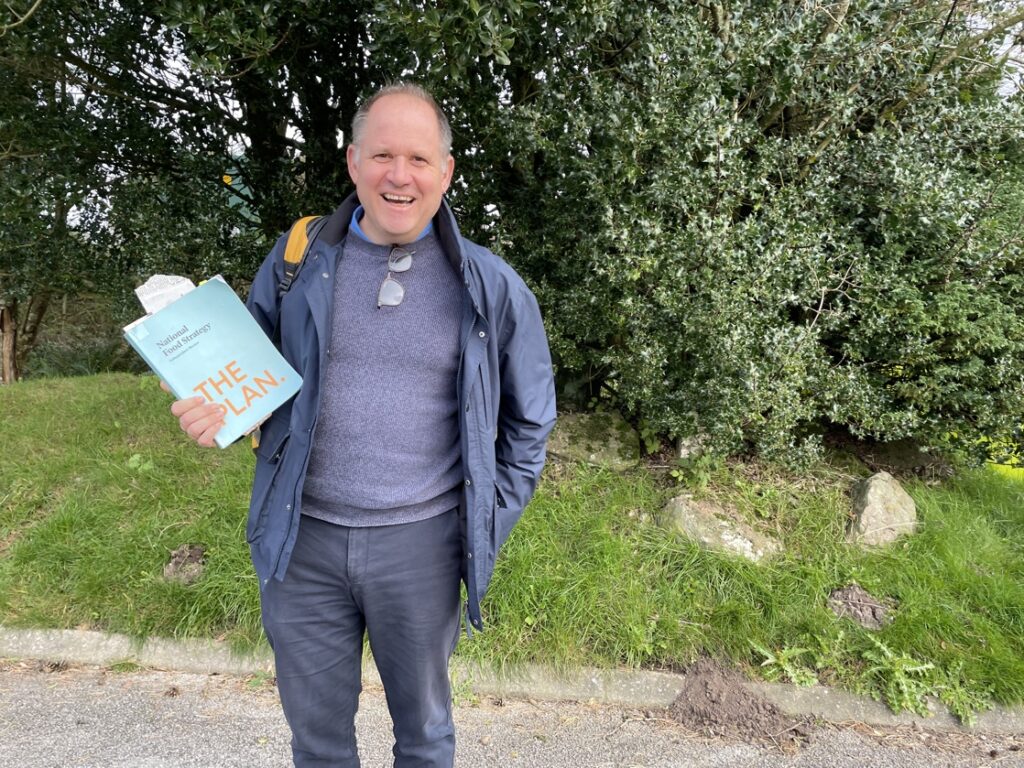

Imagine if the government gripped parts of The Food Plan (Three Compartment farming model, dietary nudges on meat), suggested a Multifunctional Land Use Framework consultation, and outlined a funded road map on how agriculture achieves its net zero targets. It might help us to acknowledge the trade-offs required, while not defaulting to a somewhat meaningless expression “two sides of the same coin“.

It’s time to be more honest with ourselves.

Here are some frank and creative ways to think on the issues:

HTP

H is for humility (and honesty!). Not everything has gone right over the last 70 years across the countryside. The countryside has been the frontline for post-war and CAP policies. Whether mechanical weeding of organic oats (think ground nesting farmland birds) or clear-fell forestry (think soil erosion) – both involve environmental trade-offs. Away from the glare of social media, it’s as hard to keep hedgerows in prime condition, dog walkers away from sheep, lynx closer to deer as it is to conserve curlews when abutting up to silage production, badgers, and trees.

Perhaps an acceptance of these ‘wicked problems’ might then help understand them better.

T is for tolerance when truth and reconciliation are tough to find space for under an unrelenting spotlight. An agrochemical rep can love wild bees. A gamekeeper look after hen harriers. A farmer can grow trees. A scientist get closer to land managers. Environmentalists lament the lack of woodland management and slow rate of tree planting yet fear firing up chainsaws or planting squirrel resilient ‘nurse’ conifers into native hardwood plantations. A single-issue short term campaign does not a long-term land use strategy make! Nor help build trust.

And in all this ‘just transition’ please do keep a weather eye on the mental health of those working in healthy-looking green spaces.

P is for pragmatism. There’s little time for dogmatism. Or idealism. Or ideology. Locating and then moving to find space to enable action is vital; while all the while seeking to harness diversity of views bring people with you.

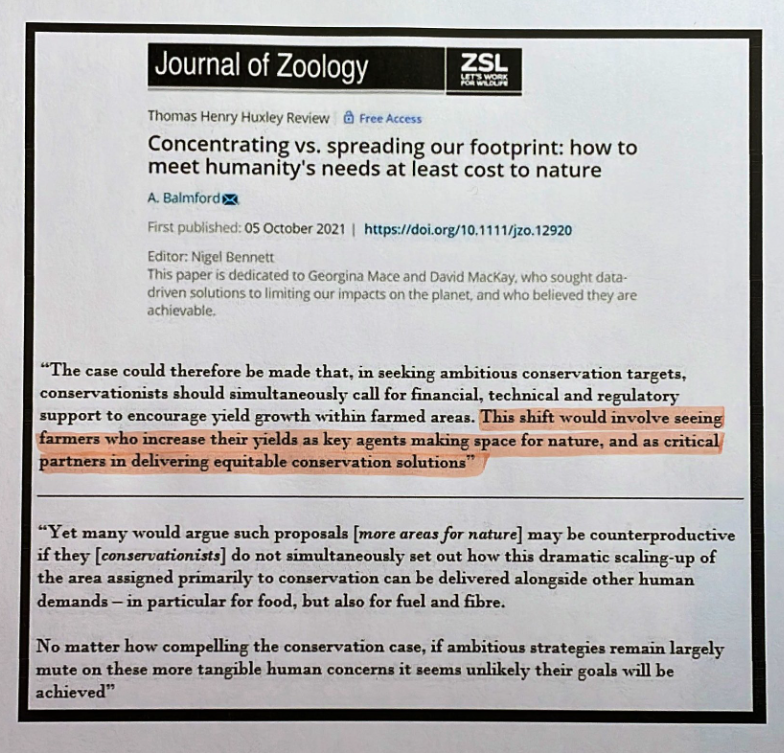

Jack Bobo said on getting the pragmatic language right: ‘don’t tell farmers what they should do… but what they could do’ and “use the language which resonates with farmers”. This then enables them to deliver a stronger interdisciplinary role effectively as conservationists – not just food producers.

Nick Cave mirrors this:

“show that we have the necessary willingness to hold two contrasting ideas in our hand at the same time”

His New Year message for 2024

Cunning conservation

I’ve really enjoyed moderating events. With my long memory, diplomatically ‘reading the room’ to enable the quieter voices to be heard. This may involve moving furniture to put people together, orchestrating an ‘open mic’ forum and framing questions to enable people to say what they need to say (not just what they want to say). All of this can help open up previously unrecognised common ground over conservation.

This isn’t about policy. Especially when politics is so weak and wonky. This is about diversity of people. Upskilled for a modern countryside. Even with an uncertain landscape, we can configure new skills, repurposing old thinking to adapt the building of resilience across a changing multifunctional countryside. (And perhaps repair some of dysfunctional loss of trust between ourselves.)

So I propose we become bravely creative in moving forward together into 2024 and beyond.

“Our responsibility is to do what we can, learn what we can, improve the solutions, and pass them on”

Richard P Feynman (again) And a conservation scientist below:

ps – this is an adaptive blog open to updates at any time: do leave a comment! Updated 26/2/24, 29/3/24