A short two-part conversation with Professor Sir Charles Godfray. Part 1 is about the role of scientists as honest brokers/advocates and scientific research around environmental issues. Part 2 is about land use, farming, food, sharing/sparing and trade-offs. (The two parts are not mutually exclusive)

This is a lightly edited version from a transcript of a recording from our meeting in Oxford in January 2023 and all the links/refs/pictures are the sole responsibility of myself.

Part 1 – science

Rob Yorke (RY): How do you see the role of academics and researchers on land, environmental, food, farming issues?

Charles Godfray (CG): I think academics can be valuable in several ways. One is in an honest broker role looking at the evidence in a particular area to sift and summarise the present evidence in as policy neutral way as possible. I think when academics do this, it behoves them to be very clear about not only claiming to be policy neutral, but to really to try and be policy neutral.

Another role of academics is that of an advocate. When academics move into this area, they take their specialist knowledge in their field and mesh it with their own personal worldview alongside their understanding of cognate areas. So, for example a natural scientist, in adopting an advocacy position, might also consider their view of economics as this can add to the quality of the ‘national debate’ about a topic.

RY: Even as the media may selectively quote scientists advocating their views…

CG: It is important for academics to be honest about when they are being advocates, as opposed to objective reviewers of the evidence and do not abuse the authority of science in promoting a particular advocacy role.

Social science’s role

RY: How easy is it for academics to be ‘honest brokers’ when emotion might ‘tempt’ them from viewing hard empirical science with an objective eye?

CG: I think there are two different processes here. The first is sorting out of the science, the fundamentals of trying to work out how nature works. Though some social scientists might say that even this is value-laden as individual scientists bring their own values to this work.

The second one is when scientists feed into policy making which often involves social sciences – which may include a spectrum of economics and political economy – which, when you live in a democracy, are the things that must come together.

RY: Does the phrase ‘follow the science’ sometimes distract from democratic decisions?

CG: I am not keen on the phrase ‘follow the science’. To me, the important thing about those formulating policy is that they do not contradict the science – they do not say ‘black is white’. If the policy is consistent with the science, this enables the same evidence-base seen through the prisms of different worldviews, and taking account of different evidence from the social sciences, to lead to very different policy outcomes.

The role of the scientist is to advise policymakers on the science to enable them to create policy based on a range of evidence within a range of other relevant issues including political worldviews.

On bees and badgers

RY: You have undertaken a number of restatements on high-profile issues such as bovineTB (BTB) and neonicotinoids. How important are these restatements in expressing the certainty and uncertainty of the science?

CG: Restatements are one way to attempt to do an ‘honest broker’ summary of all the known evidence available to date. The first one we did on bTB involved deliberately getting people in with different advocacy viewpoints. I remember a colleague saying at the start; “This is either going to be tremendous fun or a complete car crash”

After a rocky start with some participants ‘squaring up,’ they then ‘got it’, by that I mean they got that we were not trying to make policy prescriptions. We were trying to lay out the existing evidence-base, much of it uncertain, and then seek to clarify those levels of uncertainty. As soon as people got the aim of evaluating certainty around what we knew, then it became easier for people, who had different advocacy positions, to work together.

RY: Could restatements be used more often to help society understand environmental issues, incorporating uncertainty and from a range of viewpoints?

CG: Where there is a contentious question of policy relevance, the government can suggest an external expert restatement. They are a lot of work to do, so you only really want to do it in areas which cannot be done by a simpler manner. Restatements can be criticised for not being algorithmic and relying (purely) on expert judgement; which when ten or so people come together, inevitably comes with a spectrum of subjectivity. I think overall the value of restatements is where the independence adds legitimacy to the ‘honest broker’ relevance of the review.

Part 2 – land use

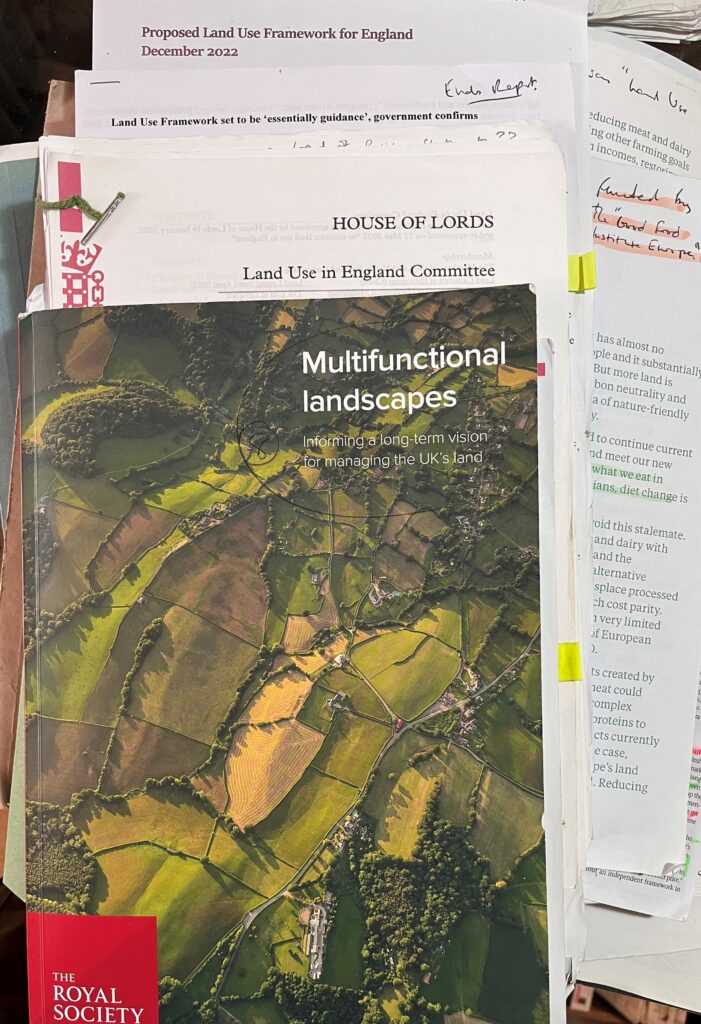

RY: I am aware you have completed a report on multifunctional landscapes: how does that fit with a long-mooted land use framework?

CG: Our Royal Society report on Multifunctional landscapes concluded that a land use framework is a good idea. Our report is trying to be helpful, rather than prescriptive, to outline some of the principles which might make a land use strategy work on the ground. The House of Lords report also recommends a land use strategy, and quite appropriately for parliamentarians, it also talks more about how its structure could be set up.

RY: We might have to decide between different biodiversity – say trade-offs between farmland and woodland nature – would better metrics help?

CG: Metrics are hard. But one of the main reasons the Royal Society and House of Lords reports both recommend a land use framework, is we must get down to considering trade-offs as part of making hard decisions. While, increasingly, there are analytical methods to help us try and understand how we can get multiple goods from the landscape.

And yes, you are right, there are ineluctable trade-offs. There is farmland biodiversity, maximised from having low-input farmland, and non-farmland biodiversity which does not exist on farmland but which you get from creating ‘natural’ habitats such as marshland or woodland.

Land choices

RY: With a crowded farmland dominated isle, can we have it all?

CG: I think we need to be asking some difficult questions about what we want from farming. A conservative estimate is that we will need 30% more food globally by mid-century, though I suspect it is more likely to be 50%. So, what should the UK do in the face of that increased demand for food?

I think there are three separate arguments one could make:

- (1) we are a high-tech country with one of the most efficient agricultures in the world. Could it be even more efficient, and should it contribute to meeting that increased global demand.

- (2) we are a country with a relatively stable population – should we continue our current rate of food production, neither increasing or decreasing it.

- (3) we are one of the most ‘biodiversity-depleted’ countries in the world, should we de-intensify our farming, produce less food, and seek to increase our biodiversity.

RY: Who is weighing up these arguments?

CG: The government – and there are caveats along the way. If they want to de-intensify (3), they must work out from where our food is going to come from. It is not good enough to say more is going to be produced in ‘factory farms’ – though I do think there will be a bit of that – but that essentially more food will come with imports.

If we are going to increase domestic food production (1), then we are going to have to square that with our commitments for biodiversity, carbon, ecosystem services, natural capital etc.

From the previous government’s response to the Food Strategy Plan, it would seem to date to be continuing on the current trajectory (2).

Meaty planetary issues

RY: I sense this discussion is linked to society’s dietary changes; seemingly an unpalatable matter for any government to tell people how to eat?

CG: Yes, and as part of this inevitably we are going to have to eat less meat [especially red] and that is going to affect the farming industry.

RY: You are referring to ‘eat 30% less meat’ out of The National Food Strategy (Dimbleby’s report)?

CG: Yes, and some would argue that that is an underestimate. Another issue is that the [farming] industry hasn’t appreciated the amount of investment and innovation going into meat and dairy substitutes. It is far from certain, but if I was to bet, I would say in ten years’ time most of the processed meat in sausages, patties and things like that would come from non-traditional sources. So, I think that is going to be a genuine disruption of the livestock industry and I worry a bit that it has, to a certain extent, its head in the sand at the moment.

Boggy Fens

RY: Land use is not just about livestock, it might also include rewetting lowland peat farmland to provide public benefit from carbon sequestration?

CG: I would rather agree with that.

It is very important how you frame it. All land must be ‘productive’, but now not only in terms of food, fibre and fuel, but also in terms of ecosystem services public goods. So, if land is to ‘produce’ biodiversity, you must ensure it is good for biodiversity in the first place. And arguably the same applies to food production.

Trade-off land uses

RY: This might bring us to ideas around ‘land sharing and sparing’ – how do you view these issues?

The Food Strategy, under Chapter 10 and Recommendation 9, proposed the ‘Three compartment model’ (page 96 of The Plan). This built on from work by Professor Andrew Balmford and views the three compartments as a continuum of different land uses at both farm and landscape scale. At the sparing end of the continuum it includes some land out of farming, as that is the only way we are going to restore substantial biodiversity and head towards net zero by 2050.

My slight concern about some of the sharing arguments is that by seeking to share land everywhere, you do not get the best biodiversity and you do not get the best food production.

RY: Would a land use framework assist land managers in optimising land use?

CG: Once you are clear about what you want to do, and considering the trade-offs, you ineluctably get to something that is not sharing land for both food and nature everywhere.

If you think that the UK has only got a tiny percentage of unmodified habitat now, taking a relatively small amount of land out of agriculture could substantially increase our biodiversity and carbon storage.

RY: And the current farm spending?

CG: This is about keeping people on the land providing different outcomes. My view is that with circa £3 billion we currently spend on farming support, this is reallocated for producing public goods across the shared (with nature) and spared (for nature) continuum of land use. The suitable land managed chiefly for food production gets very little public payments, whereas on other land where you take a hit on yield to increase other output/functions, public funding is increased.

RY: A new role for some farmers?

CG: It would mean a different way of thinking for farmers, not only as producers of food, but as stewards of the land and producers of other land-based environmental products.

ENDS

- additional listening – BBC Radio 4’s The Life Scientific with Sir Charles Godfray, March 2024

- an online discussion ‘Resetting our relationship with nature in a post-COVID world‘ with Prof Charles Godfray and Prof EJ Milner-Gulland, Sept 2020

- further reading – “Sustainable agriculture and food systems; comparing contrasting and contested versions“; with more links to the topics above here.